I loved my work at The Free School. I started reading books by alternative education pioneers like John Holt, Ron Miller and A. S. Neill, the founder of the Summerhill School in England. I went to conferences on Alternative education and engaged in fascinating discussions about all of the different models. I learned how to teach effectively, how to reach reluctant students and how to let go of some of my expectations for them. I also learned how to help troubled students deal with their emotions in a safe and healing way. I learned a lot about myself and was forced to look at my past traumas, seeing how they affected my reactions to things in the present. Although I felt as though I had finally found my calling, I also struggled with interpersonal issues in the school. In the early years of my teaching there, an astrologist came through town and offered readings to the teachers. I had experience with astrologers before, including the one who did a chart for Jessie when she was an infant and gave me valuable advice concerning her future health. I decided to go see what he had to say. The most important thing he told me was that, despite the differences I might have with the other staff members and members of the school community, being at the school was a valuable opportunity for me to learn how to work cooperatively in the midst of discord. He said that I would have serious struggles within this community but would come out stronger and wiser as a result. He couldn’t have been more right. I was already struggling with practices that I saw as cultish. Most of the teachers, except for me, lived in the immediate neighborhood and spent most of their time together. Their children all played together and often left out the kids who were not in that neighborhood community. The adults all belonged to an emotional support group that met once a week. I was pressured repeatedly to join the group, and I kept refusing. For one thing, I made a very small salary and spent five days a week in the school, many hours at home preparing my lesson plans or thinking about my students and how best to help them as well as a two to three hour, sometimes more, meeting once a week to talk about the students and other school business. In addition to that, there were board meetings once a month. The teacher’s meetings and board meetings were hard. They were often used to call out someone’s attitude or behavior. They were also used to solve personal problems between teachers. I saw how they would gang up on one person and keep at them until they dissolved into tears. It often felt unreasonable and abusive to me. Because I was not in the emotional support group, I was often involved in some kind of controversy at these other meetings. I would often sit there in dread waiting for someone to bring up an issue they had with me. If I disagreed with the majority, I was often attacked by the whole group. I couldn’t understand why everyone just couldn’t figure out how to get along in the spirit of cooperation and compromise. One time at a board meeting, the founder of the school asked everyone for an honest opinion about her retirement. She was older and mostly uninvolved in the day-to-day workings of the school and had expressed the desire to retire. I listened as everyone told her how valuable she was to the school and community as a whole. I listened as they all encouraged her to stay involved, but also knowing that they all dreaded having her around. The school ran well without her, and we would ask for direction when we needed it. At teachers’ meetings, they repeatedly talked about wanting her to retire but face-to-face, they backed down. When it came around to me, I told her the truth. I said that I respected her immensely and had learned most of what I knew about teaching from her. I also recognized that she had been wanting to retire for a few years but worried that the school would fall apart without her. I insisted that unless she walked away, she would never know. Unless she let the teachers try to run it on their own, we would never learn. I told her that no one was willing to stand up to her and call her out if they thought she was wrong. They were all afraid of her. I was afraid of her too, but I also wanted the school to go on. I reminded her that she could always come back if it didn’t work out. The meeting erupted! The founder, Mary, had always had anger issues, so I knew I was treading on dangerous ground. She got up and screamed inches away from my face, accusing me of trying take her school from her. As if that wasn’t bad enough, all the other board members and teachers jumped on her band wagon and started attacking me as well. I quietly got up and left. Later that night, I got a phone call from Mary apologizing to me. I later learned that after I left, and she calmed down, she turned on everyone else for not defending me. She saw that I was right. No one would ever stand up to her or question her as long as she remained in the community. She was their leader, and they were like sheep. The next day, I was drowning in apologies from everyone, but nothing really changed. I was a rebel and still the outsider, and they remained sheep. Unwittingly, I became the conscience of the school, continuing to call out wrongs that I saw and being the “bad guy” more often than I would have liked. I liked the premise of the school and respected the model. However, it was a different thing in practice. I saw some kids falling through the cracks because there seemed to be no push at all for them to learn. I became aware that this model worked well for the ones who were self-motivated, so I quickly learned how to trick the others. For example, I had one student who came from a violent home and refused to do any schoolwork at all. School was a refuge for him and nothing else. He was ten-years old and couldn’t read or write and knew almost no math. One day, I asked what he wanted to do for work when he was old enough. He told me he wanted work at Stewarts, a local convenience store chain. That afternoon, I stopped by and picked up a job application. The next morning, I handed him the application to fill out. He looked at it blankly. I asked him if he planned to have them fill it out for him at which point, he looked downcast and decided that maybe learning to read was not such a bad thing. Next, I asked him how much of a salary he would need to survive. Again, he looked at me blankly. We talked about rent, utilities and food expenses. That year, he learned to read and write and do basic math. Unfortunately, although he did learn these basic skills, everything else was against him and he ended up in jail later in life, just like his father before him. Working at this school was often as heartbreaking as it was heartwarming. I couldn’t change the conditions in which these kids lived. I loved the fact that there was such economic and racial diversity in the school, but it was also difficult emotionally. It was also hard to go home to my own kids after dealing with serious behavior and emotional issues all day while trying to help educate. Although I believed in child-led learning, I didn’t believe in letting these kids just run wild, distracting the other kids and disrupting their learning. In my classes, I found that I did have certain expectations. Every morning, we did journaling. Those who didn’t want to write or draw in their journals were expected to sit quietly and respectfully while the rest of us did our work, me included. To me, child-led learning meant that they would tell me what they wanted to learn and I would help facilitate that learning whether it meant learning it myself and passing on that knowledge or finding someone else who was more qualified than me to teach it. However, I also recognized that sometimes kids just had to have a year off to do nothing. Time and again, I saw those same kids eventually come around to classes and become increasingly engaged. I had one student who spent most of one school year covering the top of her desk with white glue. By the end of the year, it was a couple of inches thick. Another student, the daughter of two lawyers, also refused to read. She was a wonderful artist, so we let her spend the year doing art. When she finally learned to read at age twelve, she surpassed the others in her class. I never had a problem with letting the students decide what to do with their day. I only tried to stop mayhem from happening. They were allowed to go to the park and play hard, just not in the school building. Every morning the school day started with breakfast then exercises and a school-wide morning meeting. I loved the morning meetings but hated when it was my turn to lead exercises. I didn’t mind doing them, but a lot of the kids didn’t enjoy it and were resistant. The teachers all took turns, which was fair, but I struggled with being creative enough to keep them engaged. The things that I enjoyed were boring to them. Maybe they could sense my own resistance. Whatever it was, I dreaded it every week. However, years later, when the school decided to do away with it, I also missed it terribly. I felt that although I struggled with my role, it was an important way to start off the day. Now there was no sense of community building first thing in the mornings. During the twelve years that I taught in this school, I learned as much as the students did. It’s not always easy to sit back and let your students take the reins. It takes a lot of trust in their natural instincts but also requires a teacher to be intimately involved in their lives, learning how to coax ideas and suggestions out of them, learning to listen to them intently. This means not only listening to their words but listening for the underlying message or watching for clues in their body language. It means being aware of even the subtlest changes in their demeanor or behavior. I learned how to listen with my whole being, not just my ears. I learned to encourage the show of emotions in a safe way, both to the student involved and the others around them. I learned how to let them make their own way without abandoning them but rather being a safety net in case they fell. I learned to trust children to know themselves, their strengths and limitations. And I learned to trust my own instincts as well. I also learned very practical skills for dealing with damaged children such as safe and effective restraining holds. But most of all, I learned patience and trust. Trust in them and trust in myself. After a few years teaching there, I became a co-director responsible for the “upstairs” which was Kindergarten and preschool. I also started coordinating the school lunch program and cooking breakfast in the mornings. I loved coming in early, before everyone else arrived and settling into my day by preparing the food. Breakfast has always been one of my favorite meals to make. Unfortunately, I was not making enough money at the school and started looking for extra work. I answered an ad for a piano teacher at Hilton Music in Troy and got the job. I would go in early on Saturdays and work all day, leaving the kids home with Paul for the day. I was excited to start this new job and get back to my music roots. I also realized that I would not last there forever and wanted to use my new teaching skills in a different venue.

0 Comments

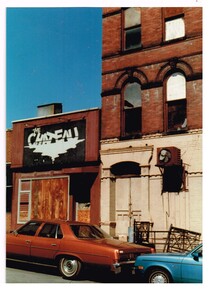

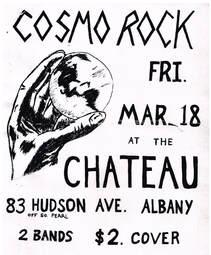

Toward the end of that schoolyear in 1984, I noticed a slight curve in my daughter’s spine. She was only eight-years old, but I was always concerned about passing on a genetic flaw that had almost crippled me. As a result, I checked my children’s’ backs regularly. Back in 1966, in the spring of my 7th grade year, I was diagnosed with scoliosis which is a curvature of the spine. This was devastating news. As a child, I was extremely shy, definitely scared and a little odd. In our first neighborhood, there were other neighborhood kids to play with. Back then all the kids in neighborhood spent the days outside playing together. When I was ten-years old, my parents bought their first house and moved us to a different neighborhood. We still lived close enough for me and my brother to go to the same Elementary School. Then a couple of years later, I started Junior High School. This would be 7th, 8th and 9th grades. This was a huge change for me. I’d never had many friends but quickly made a few during the mile walk to and from school. I am still in touch with one of these friends. At that time, we felt as though we were entering the teenage world, even though we weren’t teens yet. We smoked cigarettes together, a couple of us shoplifted, we explored abandoned buildings, flirted a little and fought but basically, we just had a lot of fun being a little bit delinquent. I was also trying new things in school. I thrived in music and art, enjoyed most of my classes and, for the first time, felt excited about school. I discovered gymnastics during my gym class and was trying to negotiate for lessons with my pre-teen dream of someday being in the Olympics. And there was my Girl Scout Troop. I was a Girl Scout from Kindergarten or 1st grade on through High School and loved it. I guess most troops did a lot of sewing, cooking, first aid, you know … girl things. My troop did those too, but we also went on amazing trips. We went hiking and camping regardless of the weather. We learned survival skills like how to build shelters, build a fire in the rain, cook food over an open fire and find wild foods. We went white water rafting on the Delaware River; we built a little over a mile long wooden walkway through the wetlands at The Bartlett Arboretum in Stamford, Connecticut with a Reader’s Digest Grant, spent a week camping in the Adirondacks and went on a month-long camping trip from Connecticut to the mountains of Wyoming. We had a charter bus that transported us from place to place. We camped in Canada and many northern states before reaching Wyoming where we spent a week camping in the Rocky Mountains. It was the trip of a lifetime. So, now it was the spring of 8th grade. There was one more year in Junior High before starting High School. Then, my parents suddenly decided to take me out of public school and enrolled me in the all-girls Catholic High School to afford me a “better” education. I was devastated! All of my friends would be going to a different school. Then, I found out about my scoliosis. Ugh! But really, how bad could it be? I went through a battery of tests that spring, each one giving a grimmer prognosis. Finally, they decided that I should see a doctor in New York City. That doctor determined that there were two severe curves and recommended a steel and leather back brace that stretched from just under my chin, lifting my head slightly, to just below my hips. I spent a week in the hospital away from my family while I was examined repeatedly by various classes of doctors at this teaching hospital and was finally fitted for a Milwaukee brace. I wore it 24-hours a day with an hour allowed for showering a couple of days a week. It was supposed to stop the progression of the curve which would have eventually killed me, so I had no choice but to do this until my bones stopped growing. For me this meant just before graduating from high school. Those years were a nightmare. I was without my only friends and was relentlessly bullied but also bored to tears. Sister Kelliher, the social studies teacher, must have been ninety-years old. She could barely stand and had a voice so weak and shaky that I never understood a word she said. Another teacher, Mrs. Grant, looked like a zombie or maybe a vampire. Her face was long and thin and pasty white with bright red lipstick and dark circles under her eyes. She had orange hair that was parted in the middle and hung straight down on both sides. She wore a dull colored dark shift that accentuated She spoke in a monotone. She was the Latin teacher. It was too bad because I liked languages and wanted to study Latin, but I couldn’t focus on the class at all and did nothing but daydream. Latin was a required course for two years. I had to be tutored both years during the summer to pass. Worst of all, there were no music or art classes offered in the school, and those subjects were my lifeline. Because it was a Catholic school, most of the kids came from Catholic Elementary schools and entered high school with plenty of friends. Although, my family was of Catholic faith, we weren’t all that religious. We went to church on major holidays and when it was time for me or my brother to do some coming of age event. I had gone to Catechism classes and had also gotten thrown out twice for asking the wrong questions. All of the students in afternoon Catechism were public-school kids who weren’t getting religious education in school. I entered the school knowing one set of twins who lived in the neighborhood. New kids were immediate targets. I was not only a new kid, but I was different and disabled. In my Sophomore year, classes became co-ed. Conditions in my high school were already bad enough with the other girls. Now they were introducing boys into the mix. Now the girls got nasty and many of the boys were bullies. It was so bad, those of us being bullied wouldn’t even sit together in the cafeteria for fear of being targeted. We tried to disappear in the crowd, a skill I am still good at if necessary. There was one sweet but quite shy boy, who was also bullied so badly, he committed suicide. Another boy a year ahead of me took a gun to the roof of the school and shot it randomly injuring a a student and a teacher, then he shot himself. Although there were no music or art classes until my senior year, I managed to survive with my music. Now, I was worried about Jessie. Had she inherited this scoliosis which can be passed down through the generations? My grandmother had been very bent over. Think Quasimoto. Jessie also struggled making friends, and I couldn’t face a repeat of what I had gone through with my daughter. I got her an appointment with a specialist. She did indeed have a slight curve, but nothing that needed attention. However, he wanted to examine me. I insisted that I was fine. I explained that I had already been treated, and the curve was stable. He asked a lot of questions, including how much discomfort I was experiencing now. I answered all of his questions then, at his insistence, agreed to an x-ray. He also sent away for my old records. A week later, he explained that the curvature in my spine had started up again, probably because of a combination of gravity and childbearing. He estimated that I had about ten years to live unless I had surgery. It wasn’t much of a choice as I hadn’t yet come into my prime. The surgery was scheduled for summer, after school ended so that I could finish my internship and have my kids go to their grandparents. The operation would be bone grafts taken from my hip and the placement of a Harrington Rod, a flexible steel rod inserted the length of my spine with assorted hooks and wires. They predicted a 6-week hospital stay and at least nine months in another back brace, not as invasive as the first one. I started looking into herbs and vitamins immediately. I had been utilizing alternative medicine for quite a few years by now and knew that it could only help. I started on a daily regimen of vitamins and had family members sneak them into me once I was out of ICU. I had asked the doctor to give them to me, but he refused insisting that they wouldn’t help anyway, so my outlaw instincts came out. Paul usually came to visit once a day but had a phobia about hospitals and always stayed less than an hour. Because my kids were staying with their grandparents while I was hospitalized, my parents brought them to visit a few times. Mostly, I was alone for weeks, doing a lot of reading and yearning to get out. I managed to leave the hospital in three weeks and only wore the brace for six months, reducing the projections by a lot. To say the medical professionals were surprised is an understatement. I usually know what my body needs to heal and am always determined to have my way. I got out of the hospital, two inches taller, in time for the big Rok Against Reaganomix concert in Washington Park (Albany, NY) that summer. General Eclectic was on the bill. Everyone was concerned about me doing this performance. I’d only been out for a couple of weeks, but I was determined. Music is the one consistent thing that’s healed me and kept me going. I was not going to miss this show. The stage was always a flatbed truck with rickety makeshift stairs and no railing. The only obstacle to me performing was getting up onto that stage. I was still on pain meds and adjusting to the new brace, but friends in the committee helped me up. Once there, I was good to go and sang my heart out. It felt good to be doing the thing I’ve always loved the most. I had missed it terribly. Now I could look forward to a life without pain, or much less pain anyway. I was also looking forward to being a teacher at The Free School in the fall with both kids attending.  The summer of 1983 ended too soon for us, but we were becoming well-established in this new home. I had enrolled Jessie in The Free School and, with the start of the school year, I was invited to spend as much time as I liked volunteering there with Justin in tow. Although, I had done some home schooling and taught private piano and voice lessons, I had never taught in a school. This was a different school that focused on student-led education and emotional development. It was founded in 1969 and is the oldest inner-city independent alternative school in the United States. The school was tuition-based but was mostly supported by rentals. The school had bought brownstones that needed to be rehabbed at extremely low prices, then fixed them up and sold a few to teachers then rented the rest for reasonable prices. I was fascinated by this unusual model. I mostly stayed in the upstairs part of the school which housed the kindergarten and preschool. I didn’t want to encroach on Jessie’s experience, a decision I came to regret, but I also had my three-year old with me who wasn’t formally enrolled yet as a student. The school tuition was on a sliding scale with no one turned away for lack of funds. This meant that the demographics of the students was diverse, which I liked. I wanted my children to be exposed to other children with many different lifestyles, economic backgrounds and belief systems. Unfortunately, like everything, the school had it’s good and bad qualities, and the bad ones were hidden from me for the most part. However, they were looking for teachers and, if I volunteered a couple of days a week for this school year, I could start working there the following year with both of my children attending. They also offered to let Justin attend the rest of that year. How could I refuse? I’d been exposed to alternative education in San Francisco and in Oregon and loved the concepts. I knew I couldn’t afford college and also knew that it would be impossible to go to school while my children were so young. Although I never thought I would end up being a teacher, I was drawn to it and agreed to their offer. The tactics of the director and founder were, to put it kindly, unorthodox. There were things done there that should have been reported and certainly should have been stopped, but I wasn’t aware of them at the time. Unfortunately, Jessie experienced some of this and was cautioned to not tell anyone or it would get worse, so she kept quiet until she graduated many years later. The side of the school that I was allowed to see was one in which the children learned through play. They learned history through drama and games such as role playing, being Marco Polo and exploring Asia and the Silk Road. They learned math by playing “Math Baseball.” They learned science through experiments and field trips. They learned geography by making artistic maps and going on trips to places around the country. They also learned independence and self-sufficiency by being out in the world but also through calling and attending “council meetings.”  Council meetings were one of the most important parts of the school curriculum. If anyone had an issue with any other person, whether another student or a teacher, they could call a council meeting which was run according to Robert’s Rule of Orders and chaired by a student who was elected by a majority. The teachers tried to stay out of the negotiations as much as possible only speaking up to get things moving along or to relay their own experiences. Sometimes, if the meeting seemed stuck, teachers would suggest something outlandish to heat things up. It was a powerful process. When someone called one of these meetings, everything stopped. Every student and teacher were required to attend, and the meetings would sometimes go on for days until the problem was solved. With encouragement from the teachers, the students often came up with unorthodox solutions. If a child were being left out, the students doing the leaving out might have to spend a week being alone. Or maybe the students doing the leaving out were paired up with the one left out, having to spend every minute together to get to know each other better. If two students were fighting, they were often paired with each other or a supervised wrestling match was set up. Supervised wrestling was a big part of the curriculum with strict rules of engagement. If mandated by a council meeting, the entire school turned out for these events. The belief was that these kids needed to learn to work out their issues rather than being talked out of it. We all knew that unless it was resolved in school, it was likely to be taken to the streets where there was no supervision. There were kids of all kinds attending school there including some very damaged kids from dysfunctional and violent homes who were violent themselves and tended to gravitate towards gangs and a life of crime. I learned how to restrain kids in a way that protected both them and me. I learned how to supervise fair fights and wrestling matches. I learned how to encourage the release of emotions in a safe way, and I saw these tactics work to help kids be able to learn and grow and survive their trauma. I also learned how to watch for signs of abuse and deal with aggressive parents. But most of all, I learned how to teach children effectively. It was better than any classes I had taken before or since. In working there, I became a real teacher and found an inner strength I didn’t know I had. Much later on I realized that all of the teachers were becoming educated as well as educating others. As much as I loved my work there, it was difficult working with wild, sometimes out-of-control kids and then going home with my own kids. So, I started taking advantage of the couple of school days I was allowed to be home. Jessie had acclimated to the city and, since we lived only a few blocks away from the school, started walking her brother home in the afternoons that I didn’t work. Justin, having always been a handful, and never listened to her, started running off during these walks home and doing other dangerous things that scared her. She called a council meeting at which they decided that she would walk him home on a leash. It sounded like a good solution to everyone until he started crawling on all fours, barking like a dog and embarrassing her, so that was the end of that responsibility. I didn’t really mind too much, and it gave her more freedom to do other things on those days. The school community was very insular with the other teachers’ kids not very welcoming to newcomers and the teachers too close to the situation to see what was going on, so Jessie struggled with her friendships there. Luckily, she made another friend in the neighborhood in addition to the girl who lived on the first floor of our building. Amber was a couple of years older than Jessie, but they hit it off immediately. I even got to know and liked her mother. Kathleen was a radical feminist who informed me that if she had known that she was having a boy, she would have aborted the pregnancy. I was horrified. I’d known lots of radical feminists when I lived on the west coast, but no one had ever expressed this to me before. I knew better than to try to change her mind and tolerated her views as best I could. However, by the end of the first month that we knew each other, she had turned her views around because Justin won her over. He was the first boy she ever liked. This surprised me because he was a wild child, but he was also polite and a lot of fun to be around. Annette and Chris, some of the first friends we met in the neighborhood, lived next door to Kathleen. Jessie soon started babysitting for their young daughter and also took piano lessons from Annette. When that wasn’t happening, Annette often drove me around town showing me how to find my way, teaching me shortcuts and filling me in on bits of history. I had also started hanging out with one of the Rok Against Reganomix families who had children around the same age as ours. Now there were parties and potlucks again. We were definitely settling in, and I started feeling as though I could stay here. I was making friends and was learning how to be an educator.  Paul was also making friends through his job as well as meeting other musicians. We were both involved with Rok Against Reganomix, organizing concerts at local clubs to fundraise for the big summer concert. We had also found the Half Moon Café which was quickly becoming our home venue. It was only a few blocks away and was open to booking us as a duo and with our band. We played there at least once a month, packing the place with folks congregating on the sidewalk outside when it was too crowded to go inside. More and more, it was beginning to look like we could actually be happy here. But Paul was never happy unless he was traveling and started talking about another move. I reminded him that we had promised Jessie we would stay here while she was still in school, allowing her to settle, and he wasn’t happy. His wanderlust was not giving up, and our arguments started escalating again. Luckily, our shared music always brought us back together. We played the Chateau Lounge one last time before it was torn down for urban redevelopment just before the bass player and drummer, who were also good friends, moved on to other projects.  In 1983, we were excited about our new band. We called ourselves “Cosmo Rock” at that time. Although I had played in various music groups in my teens, this was the first time I had my own band. We had no idea how to run a band, but we made a good team. Paul was always a people person. Everyone loved him. He was personable, generous with his time and resources and had a “bad” joke for every occasion. He also made friends easily. I was almost his opposite. I was very shy and because of that, often came across as “stuck-up.” In truth, I just didn’t do socializing well. For Paul it came naturally, for me it was a job. I was better at the behind the scenes work. Paul went out on the circuit and got the gigs. I made the flyers (with his artistic input) and contacted the press and radio stations. Then together we went to parties and other events, often with our kids in tow. We got some very cool and some very unusual gigs in those early days and beyond. Paul somehow heard about a compilation album coming out. It was to be called “American Underground,” produced by Mark Ernst. We decided to reach out to him. He agreed to let us submit something. It was tough choosing what song to send. We were writing a lot of songs then, and we thought they were getting better and better. We finally sent what we thought was our best one. He didn’t think it was right for the album. He was going for a certain sound. We sent another, but that one wasn’t any good either. Finally, I turned to Paul and said, “I think we should just write what we think he wants and get on the damned album.” He stood firm for a while but finally agreed. In about ten minutes, we wrote a song entitled “City Flight.” The lyrics were trite and nonsensical, but the meter and rhyming were spot on. The music was also simple and straightforward. He loved it. The release was described as electronic, rock, reggae, heavy metal, hard rock, synth-pop, blues rock, prog rock, new wave and power pop. That was not us at all, but we were determined to have Cosmo Rock on that release, and we did it. One time, we played at a Battle of the Bands somewhere in the middle of nowhere. I have no idea how Paul got that gig. Paul didn’t know anyone except the guy who booked us, and the rest of us knew no one at all. The other musicians were distant at best, although we tried to mingle. The set up on the stage was weird. The stage was long and very narrow with a slightly wider right angle that jutted forward a bit. That was where the drummer ended up because his kit only fit there. There was no sound check. Everyone just went up and down quickly. The other bands sounded fine, so we weren’t worried. We launched into our first song and realized that we had no monitors. We tried to signal and finally ended our first of three songs early to try to get them back on. We were told that the sound guy was on a break, who knew where, we had a limited amount of time for our set and had better get on with it. So, we did. Paul and I had been living and playing together for years now, and were so in sync with each other, we knew we could pull it off if only the rest of the band could follow along. We’d been with Chuck and Dave for about a year, practicing sometimes two or three times a week. We were pretty confident that we could pull it off. The second song was going along much better. We were all in the groove when suddenly, the drummer’s stool went over the back edge of the stage, tipping him over onto a table of burly bikers. Without missing a beat, the bikers picked him up, still on his stool and set him back up there. We finished that song and started the next, “Glendale Train” by The New Riders of the Purple Sage. We knew this song in our sleep. It should be a breeze. I was singing along and playing my tambourine when I glanced over at Paul and realized that he was singing the words to the chorus while I sang the words to the verse. It all worked musically, and we knew by this time that most people aren’t paying close attention to the words anyway. Nonetheless, we were mortified until the crowd went wild, and we ended up coming in third. We couldn’t understand why they loved us so much. Afterwards, as we were packing up, folks started coming up commenting on our unique style, even mentioning the drummer falling off the stage and our unique arrangement of “Glendale Train.” We handed out a lot of contact info that night. The real truth is that Paul and I were both clumsy but were also good at the “save.” I’ve knocked mics over and caught them dramatically. Not because I was being cool, but because I was falling over while reaching for it. One time, at The Chateau Lounge in downtown Albany, Paul lost the strap pin in the bottom of his guitar, causing it to swing out forward and to the left. Luckily, he was gripping it tightly in that left hand in whatever chord he was playing. He just swung it back in again, then stood on one foot, like Ian Anderson, holding the guitar up with that leg and hopping around as we finished the song. Even I had to admit, it was pretty impressive. We played at The Chateau a couple of times, but mostly we played in Schenectady where the other band members were already established. Schenectady was their hometown. Chuck and Dave had been playing there since they were young teens. We got into a couple of festivals in Central Park and a few of the local bars including The Electric Grinch. One of those nights, this guy started spinning on the floor and doing “The Worm.” Everyone in the band was stunned. Although we crossed genres, we still played psychedelic music, and we’d ever had anyone break dance to our music before. It was a little odd but sure made that night fun. A few months later we played there again, and someone asked us to describe our music. Paul answered, “Well, generally speaking, we’re pretty eclectic.” As he said that, I was looking at the General Electric neon sign and thus was born the name “General Eclectic.” As I said earlier, Paul made friends easily and, when he could, he brought them home to meet me and jam or just hang out. Most of these folks didn’t have kids, so it was easier for them to come to us. We jammed with all kinds of musicians back then. I loved it. I have always loved all genres of music, though some of it I need to listen to in small doses. But still, there’s nothing I don’t like. We also tried to incorporate many genres of music into our sets. It wasn’t unusual to see a table of punks in one corner, some country folk in another, a few Deadheads sprinkled around, some straightlaced families, we seemed to attract everyone, but not in large numbers. We started struggling a bit to get gigs because we couldn’t be pigeon-holed. In a typical set, we would play jazz, blues, pop, originals, swing, country, The Dead, punk … you get the idea. You might like a few of the songs but maybe not all of them. Paul insisted that we had named ourselves General Eclectic for a reason, and it wasn’t time to compromise our values. I was all for being an individual and having a creed, but I was also trying to be practical. I was a musician and had been gigging when I met Paul. I wanted to do that work again. Paul was jealous and wouldn’t be fun to live with if I went out on my own. So, we kept going along the same way, writing lots of new songs and finding new covers. Meanwhile, Chuck and Dave were also used to getting paying gigs. They started doing side gigs and liked that income. Paul continued to refuse to let anyone dictate what songs he did, so they eventually, and quite reluctantly, moved on. It was the end of more than a band. We spent most of our time together, not only as a band but with our families. Now, everyone got busy, and we were back to being a duo again. We looked for and found other players but also decided to keep the duo going, taking what small gigs we could get while still booking the band. I kept telling myself that this was temporary, that once the kids were older, and we had more mobility and more income, things would turn around. I knew we were good musicians, but we kept being told that our music was too varied. On the other hand, that same variety was one of the things our fans loved. I kept thinking about our friends in Oregon who had encouraged us to go to Caffé Lena, saying that our music was folk rock. I started pestering Paul about going to Saratoga Springs for an Open Mic. He finally agreed until we got to the door and saw that there was a one-dollar cover. There was no way he was going to “pay to play.” Although I understood his point, this was Caffé Lena, an internationally renowned folk club. I was starting to get mad now. I insisted on going in and raced up ahead of him. Everyone was friendly. Lena met us at the top of the stairs and took our money as Paul glared at her. We played “No Free Lunch” and “875” (or “The Mouse is Everywhere”). She loved them both and invited us to please come back again the next week. I was thrilled. Paul was not. He refused to pay another dollar the following week. No matter how much I begged him, no matter how angry I got, he never set foot in there again. He was a very stubborn man. That was not the last time I regretted not playing an instrument to accompany myself.  Finally, in 1983, Paul and I had enough money to get an inexpensive apartment in the South End of Albany. It was on Green Street, in “The Pastures” area. The city had just finished putting up a new development with two- and three-story buildings made to look like brownstones for “section 8” housing. We were eligible for one of these which meant that we would pay a percentage of our combined income each month rather than a pre-determined rent. The city was trying to spruce up the ghetto and also provide alternative housing. It was a good deal for us, so we moved in June. The city later built new homes for sale to low-income families which was a good idea in theory. Absentee landlords are always a problem in low-income neighborhoods. When people own their own homes, they care for them more responsibly and don’t have to depend on someone else who may or may not care much. In practice though, the contractors for this project used shoddy materials, and unfortunately those family-owned homes deteriorated fast. I remember walking by after only a year or two and see the façade peeling off. It was sad to see that broken promise. However, our buildings were made to last. We lived on the second floor in an apartment with three bedrooms, a long living room/dining area, a small but workable kitchen and a bathroom with a tub. There were parking lots for all of the residents and a small playground in the central yard. After too many months of living in my parents’ basement, we were excited to settle in. Each of the kids had their own room for the first time. We were in a real neighborhood, close to downtown, in the State Capital with so much to do and lots of exploration ahead. Yes! This was the adrenaline rush I love. Very soon after moving in, Jessie came running up the stairs crying that some kid had stolen her bike. He came up and asked if he could have a turn riding it, and she agreed. Then he rode off laughing. We knew nothing about this new city we were in, not the demographics or the different neighborhoods. Paul and I both grew up in the suburbs and knew how to get by on the road but living in the ghetto would be a change for all of us. Paul immediately called the police who immediately came and laughed at us. Then, seeing that we needed to adjust, they gave us some advice. Always lock your doors and bikes or keep your bikes inside. Don’t trust the kids in the neighborhood to tell the truth. Don’t really trust anyone and “Don’t go over to Morton Avenue because that’s where all the drug dealers are.” We thanked them for their wisdom, waited an appropriate amount of time, then Paul headed over to Morton Avenue to replenish our stash. It had taken a lot of smoking to get by at Mom and Dad’s! Now, thanks to the helpful police, we knew right where to go. We met a few neighbors, but most of them were cautious. The kids in the neighborhood didn’t know what to make of our kids. Justin had been raised in the country for the most part and was totally comfortable with peeing on a tree. These city kids were horrified, so I had to break him of that habit. Our immediate downstairs neighbors were hard-livers and very personable. We got along well. They had a daughter Jessie’s age which was nice for both of them. We also met a couple of Deadheads who lived a block away. They had a baby, and Annette was home with her, so we became fast friends. Before long, Jessie started taking piano lessons from Annette and met one of their neighbors who had a daughter a couple of years older than her. They hit it off immediately. Even before school started back up in the fall, Jessie had made friends and seemed to be fitting in. Then we’d see what happened once school started. When I knew that we were moving to Albany, I started looking into the local public school. After the issues I’d had with the school in Beaver, Oregon with their paddling rule, I wanted to know ahead of time what we were getting into. When I spoke with the principal of this public school and told him that we had recently relocated from Oregon, he assured me that security had been tightened up that year. They checked every child for weapons before they entered the school. I asked him to repeat himself, thinking I must have misunderstood. I even drove by one morning to see for myself. There was no way I was going to send my child there. She would be mortified and eaten alive or turned in a direction I wasn’t prepared for. I remembered that my friend from the East Greenbush town beach, Linda, had told me about The Free School. It was an alternative school located only a few blocks away from our new apartment. Not long after that, I met one of the founder’s sons who also mentioned it. We didn’t have any money for an extra expense like tuition, but after meeting her son, I decided to go visit. I immediately loved the vibe of the place. It was filled with hippies of various ages and lots of laughing, playing children. Jessie, Justin and I had visited for a week before the end of the school year, negotiated a very generous sliding-scale tuition and signed her up for the following September. That summer was a whirlwind of activity. We were back in a city with music, art and theater everywhere. We went to outdoor festivals and street festivals. And we started making new friends. One of the first events we attended was a Rok Against Reaganomixconcert held in Washington Park. It was an all-day affair with bands, solo artists and speakers. Paul and I had written a song called “No Free Lunch” about Reaganomics and approached the organizers about the possibility of performing it onstage. At first, they said no because the roster was so full which was understandable. They didn’t know who us. Then one of them asked to hear a little bit of it then managed to squeeze us on the schedule. That song became so locally popular that it was requested all the time, but we got sick of it. Eventually, we started including a coupon for “No Free Lunch” on the bottom of our posters that could be redeemed for the song. We met a lot of people that day including the bands and musicians who played, Glenn Weiser, Terry Phelan, The Stomplistics, Fear of Strangers, Begonia, The Units and more. We also met many local activists. We had finally found our tribe. One of the most fun during that day was meeting LoAnne (with WolfJaw) and Yuma. Paul and I usually wandered our separate ways at events, especially when in a new town. As I wandered, keeping my kids in sight, I met a woman and her big dog. I’ve always loved dogs, grew up with them and often owned them as an adult. This dog was special. We started talking, realizing how much we liked each other and decided to go look for our partners and bring them in on this meeting. I found Paul and almost simultaneously, we both said, “I just met the coolest person. You have to meet her/him. I know we’re going to be great friends.” Apparently, the same thing was happening with LoAnne and Yuma. We were all amazed at the synchronicity of that meeting. And we did in fact become good friends. We also joined the Rok Against Reaganomix Committee which kept us busy organizing fundraising concerts at the local clubs and the big summer concert each year. We all became close, an extended family, having potlucks and parties, with our children playing together, and some of us have remained friends for many years. |

Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed